What are Ultra-Processed Foods?

Sometimes called "Frankenstein foods", they now make up 40% of our daily diets. I've asked Dr Rosemary Stanton, Australia's leading voice on nutrition, for some insights and advice.

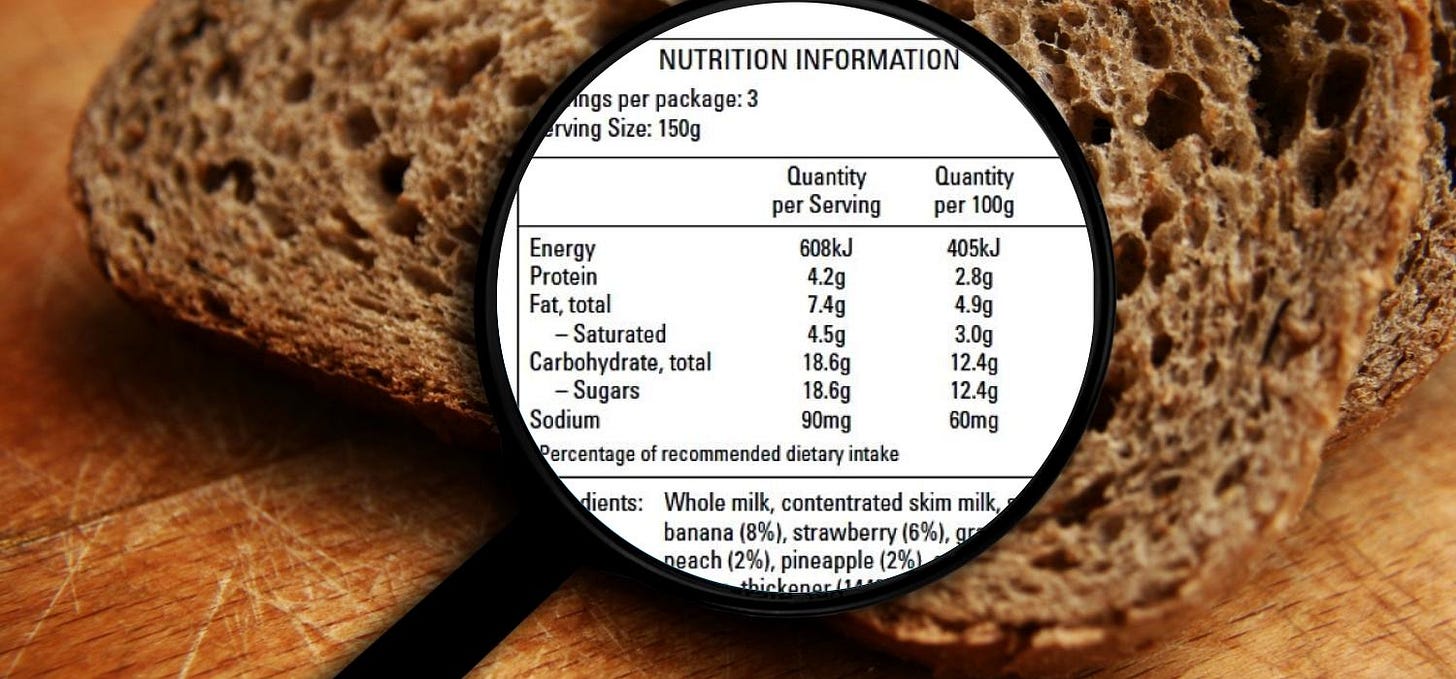

Have you ever picked up a food item and turned to the ingredient list on the label, only to get totally overwhelmed by a long list of words and numbers you can barely read — let alone recognise?

You’re not alone.

Our pantries and supermarkets are now packed with what some experts refer to as “Frankenstein foods”.

Foods often very high in salt, fat and sugar. Foods that have been built in a laboratory rather than grown on a farm, and been broken down into their smallest components only to be rebuilt, packaged and sold in enormous quantities.

I’m talking about Ultra-Processed Foods.

In-fact these foods now make up around 40% of our total diets in Australia.

With increasing evidence of health harms associated with their consumption, I asked Australia’s leading voice on all things food and nutrition — household name and trusted expert Dr Rosemary Stanton — for some advice.

Rosemary Stanton, what is an ‘Ultra-Processed Food’?

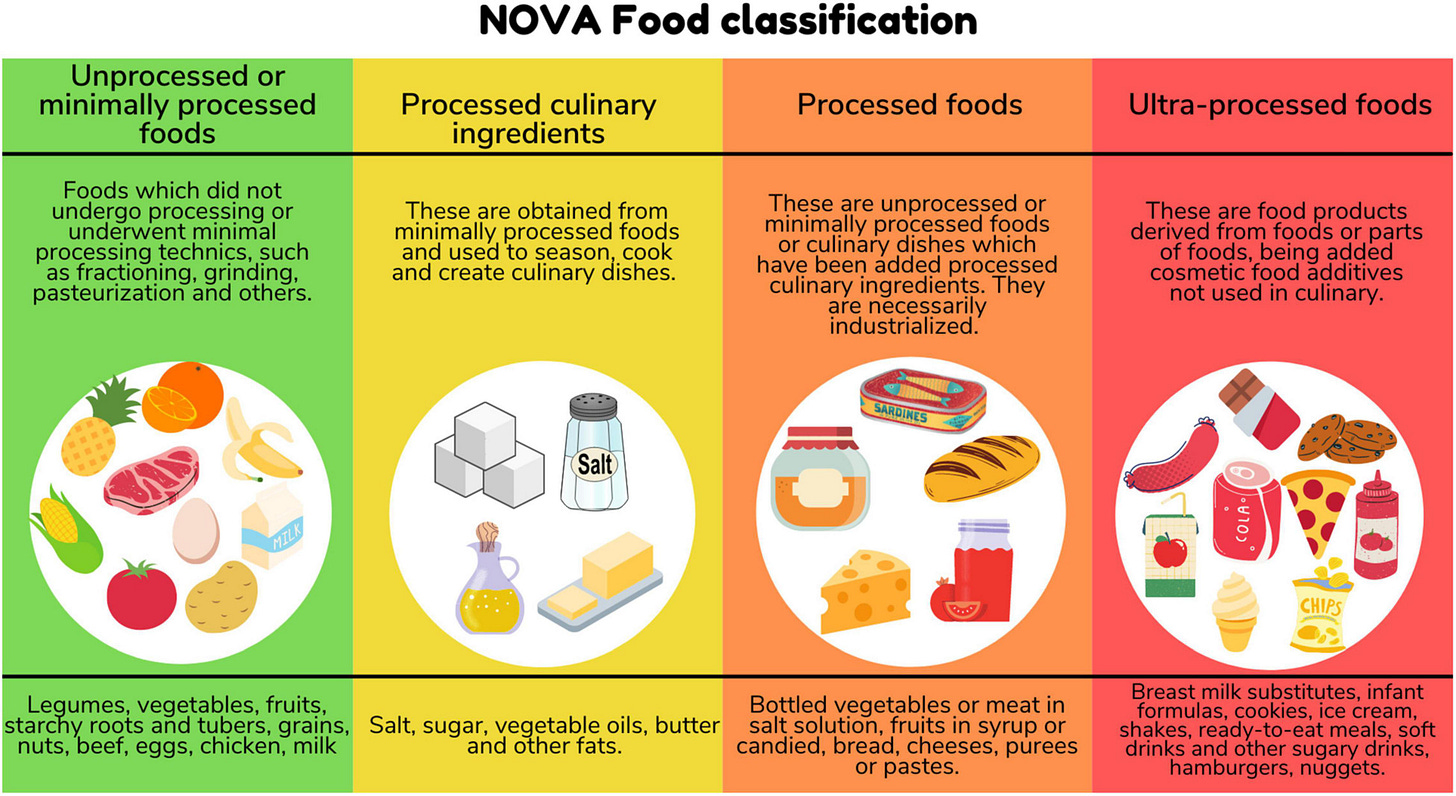

“The ‘ultra-processed’ category was originally described in the NOVA food classification system developed by health experts in Brazil.

Ultra-processed foods are formulated by food technologists, using a variety of additives that would never be available in a home kitchen. Most are high in added sugars, fats or salt, but their problems also relate to the processing and the combination of additives that make these energy-dense products convenient, often ready-to-eat and highly palatable.

Their long shelf life and relatively low price make them popular, but their lack of dietary fibre and any texture that would slow eating rate means they are easy to over-consume.

With the content of expensive ingredients minimised, the price allows for extensive and persuasive advertising.

UPFs are now so prolific that they contribute 40-50% of kilojoules for many people. Sadly, they tend to replace highly nutritious foods such as vegetable, fruits, wholegrains and legumes – all of which take time to eat.

With their minimal content of ‘real’ food, ultra-processed foods may be good for company profits, but contribute to many health problems.”

Is all processing bad?

“Processing itself is not inherently bad.

Traditional processing of foods including de-hulling, drying, crushing, grinding, pasteurisation, chilling, cooking, canning, freezing and vacuuming packaging are all helpful in supplying a safe food supply.

All these processing methods help preserve natural foods, making them safer, more suitable to store or cook in a home kitchen.”

How do I know if a food is ultra-processed?

“Check the ingredient list on the food label.

I was one of those who spent years lobbying and fighting for all packaged foods to include an ingredient list.

It’s very useful to let you know what you’re paying for and makes it easy to identify ultra-processed foods. A quick look will show a large range of additives.”

And what’s the link between UPFs and our health?

Literally dozens of studies now show a strong correlation (or link) between UPFs and obesity, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Recent studies are looking closely at whether ultra-processed foods may change ‘good’ gut bacteria in ways that would increase various adverse inflammatory reactions throughout the body.

One recent paper associated higher consumption of UPFs with cognitive decline, but we need more studies to confirm this.

The well-documented problems may stem from:

the quantity of these foods consumed;

the fact they’re high in added sugars, fats and salt, lack dietary fibre and replace healthier foods;

or possibly, the combination of additives. In Australia, all additives in foods must be approved. However, food additives are only tested for safety individually. Combinations of additives are not tested, so we do not know the effects they may have on health.

The small number of papers disputing any connection between health problems and UPFs come from food technologists of others who are funded or strongly associated (usually with monetary assistance) with the companies that produce these products.

What’s your practical advice for shoppers?

Try to minimise ultra-processed foods by ‘cooking from scratch’ where possible, using more vegetables, wholegrains, legumes and healthy fats such as extra virgin olive oil.

‘Cooking from scratch’ is difficult if one person in a household is responsible for it, so teach children to cook and encourage everyone to take a turn at producing meals throughout the week.

When shopping for packaged foods, check the ingredient panel on the label.

If it contains a long list of items, including many you’ve never heard of, can’t pronounce, or could never find in a domestic kitchen, don’t buy it, or at least only buy it rarely

Ultra-Processed Foods and health: summarising the latest evidence 💡

A recent systematic review of 19 research studies around the world examined the effects of high consumption of UPFs on human health. Collectively the studies had almost 300,000 participants.

Analysis of study findings revealed that compared with low consumption, high consumption of UPFs increased the risk of obesity, heart disease and depression.

Risk of death was also higher in five studies that followed over 73,000 participants over time.

The research team proposed several factors that may contribute to these elevated risks including the generally poor nutritional content of UPFs; compounds formed during manufacturing; chemicals in plastic food packaging; and the effects of such foods on brain signals relating to appetite.

This summary was produced by the Monash Sustainable Development Evidence Review Service from the following published research review:

· Pagliai, G., M. Dinu, M. P. Madarena, M. Bonaccio, L. Iacoviello, and F. Sofi. “Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Health Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” British Journal of Nutrition 125, no. 3 (February 2021): 308–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520002688.